At the end of September, I was informed that my friend and mentor of 30 years had been hospitalized in the ICU. This was not a huge surprise since she had stage 4 colon cancer for the better part of the last 2 years and had been in and out of the hospital several times over the last 4 or 5 months, although she had never been in the ICU before, so I had a bit of a sinking feeling. After a few groggy telephone exchanges, Cynthia told me she was being put into hospice, they had told her she had perhaps 4 months, and she was going home in a day or so, as soon as they delivered the hospital bed. She asked if I could come and be there with her and help with her birth center, which was on the ground floor of her house. So, I packed a bag and drove down to Wisconsin.

The hospital bed was delivered the next day, a Friday and was set up in the living room which had a beautiful view of the many acres Cynthia lived on and of course, the sunrise. About an hour later, an ambulance arrived with an all-female crew and Cynthia in tow. We no sooner got her settled in the living room when, true to form, she immediately started dictating who should do what and how and one of the first orders of business was getting her a glass of wine. This should not surprise anyone who knows Cynthia. She wanted to have a big meeting about dealing with the birth center, clients due beyond October and what the plan was moving forward and this could not be accomplished without wine.

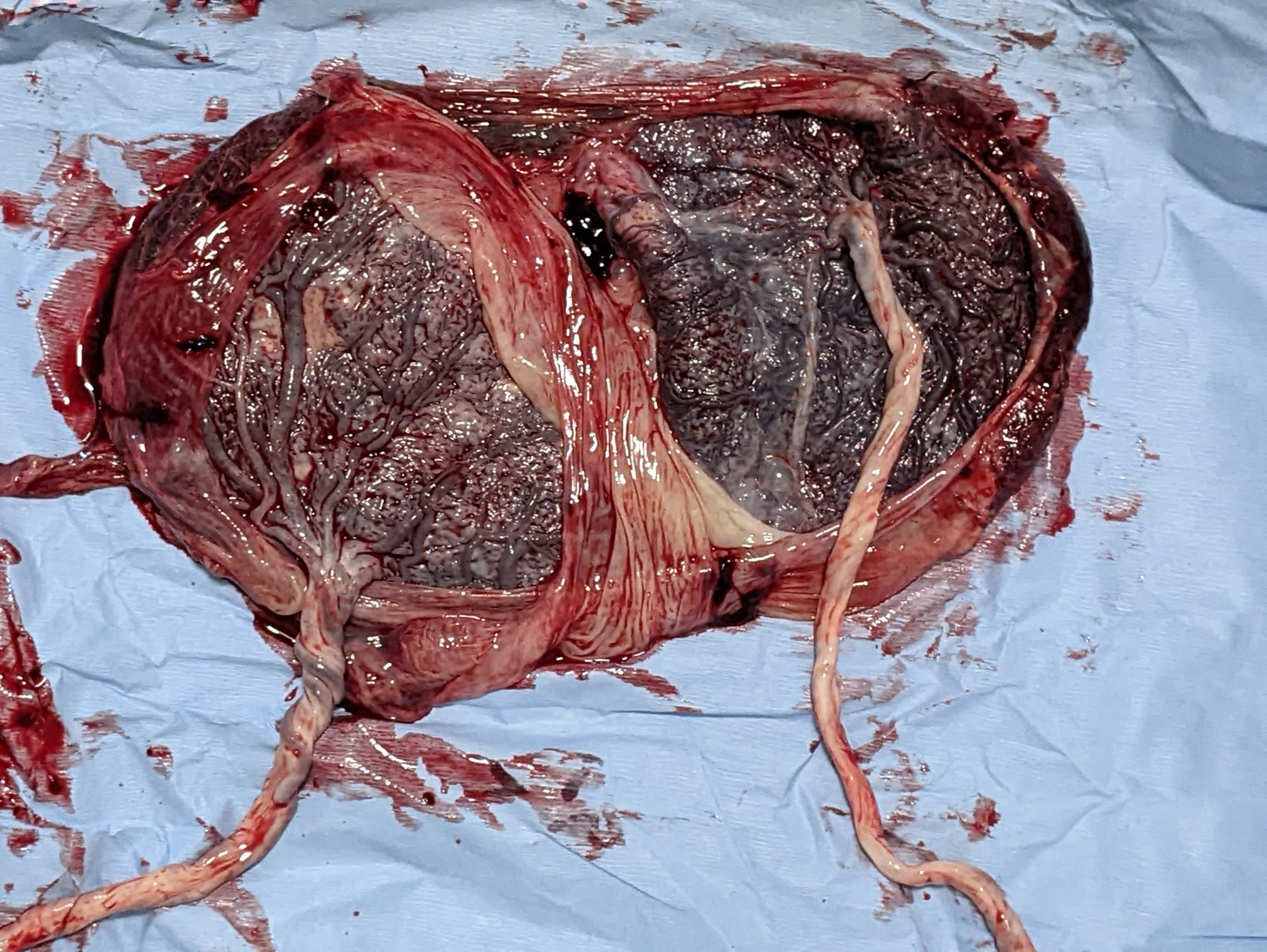

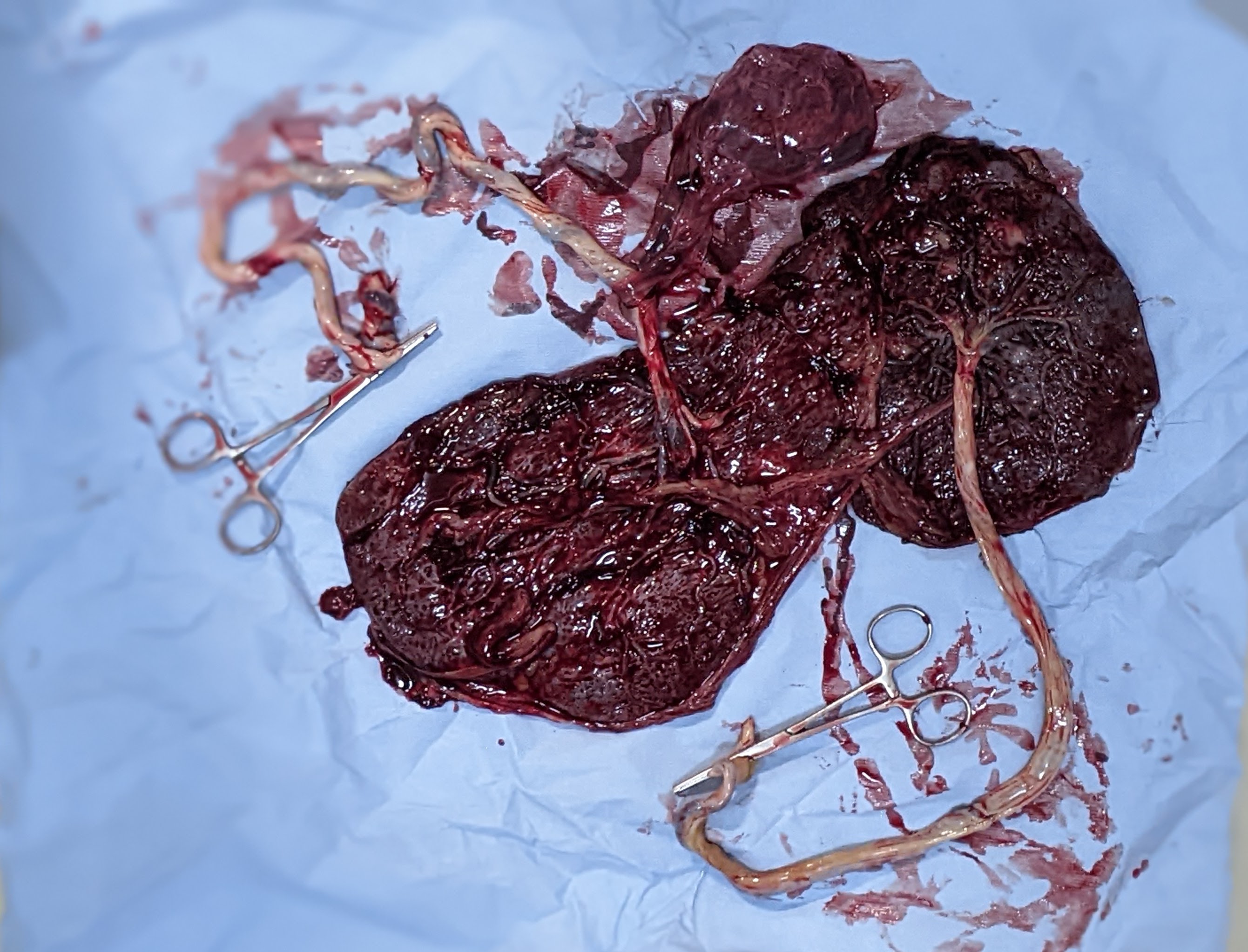

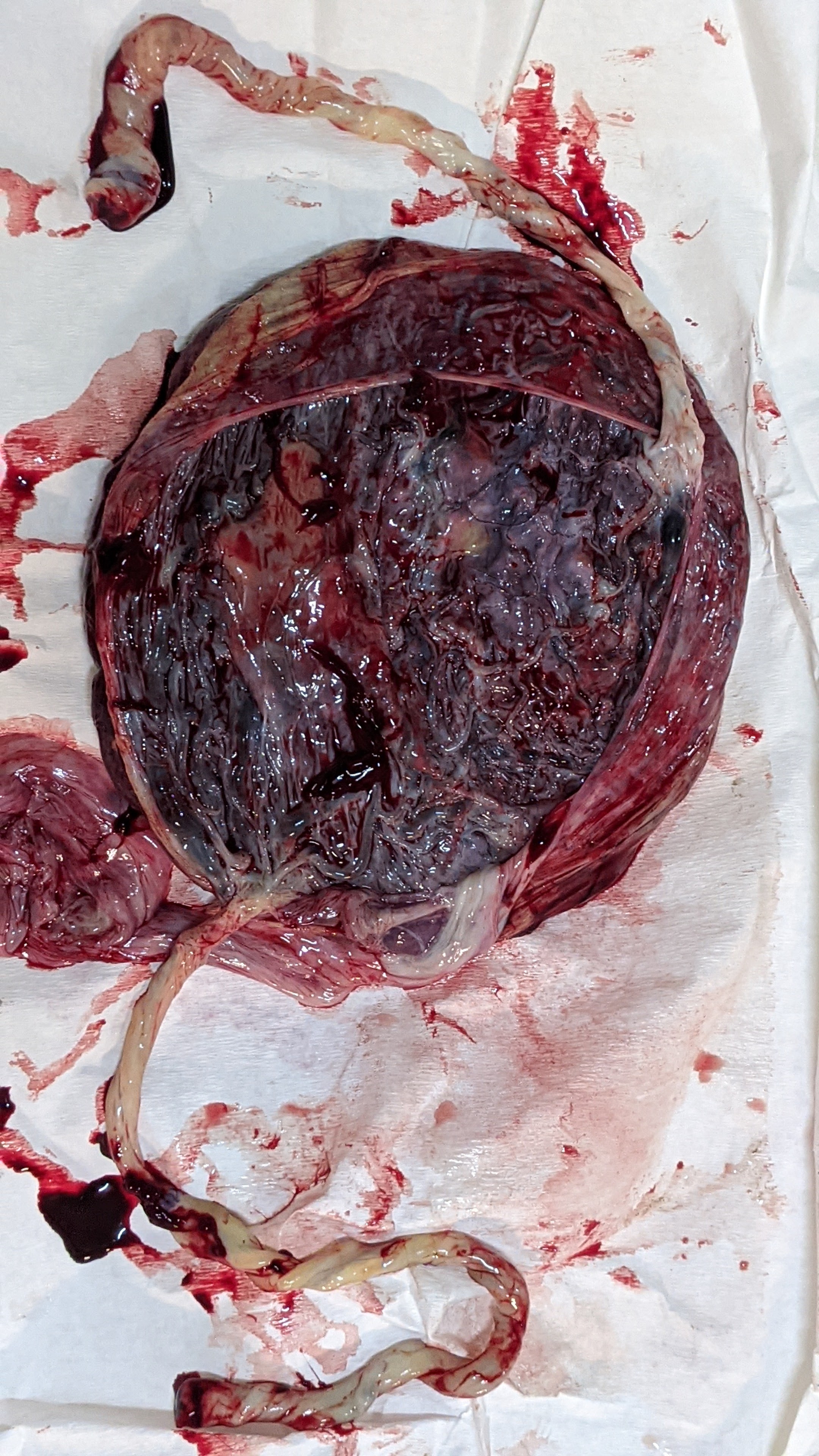

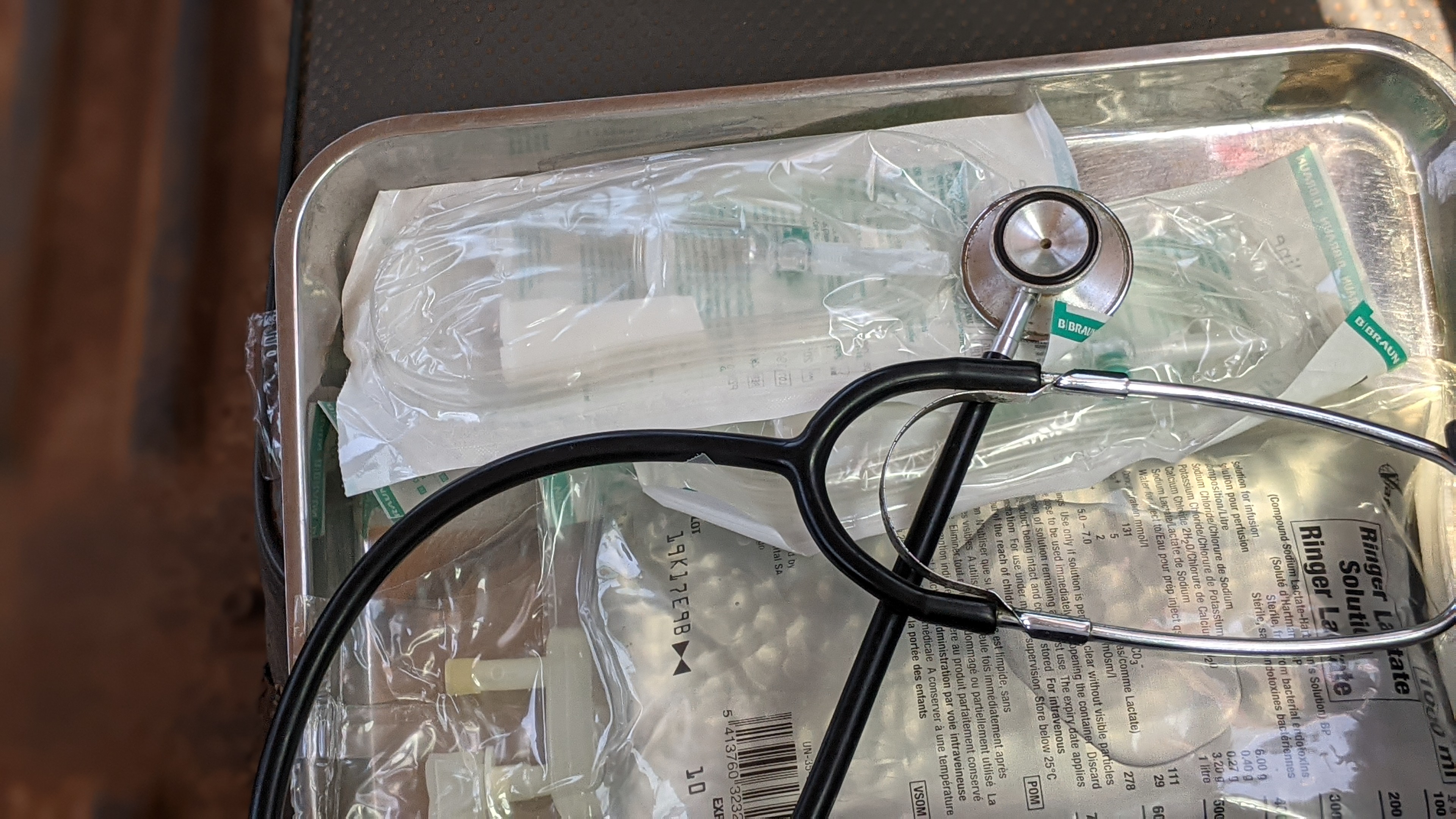

The logistics involved in finding care for all the clients of a very busy practice that served a large Amish community, was a bit overwhelming. I committed to being there to attend the 5 women that were all within the window of their birth time, 37 weeks or less. Cynthia would also need someone there 24/7 with her, so I could easily do both things. Her daughter lived over an hour and a half away and worked fulltime. She was able to come some days after work and be there on the weekends, or at least this would be the plan.

It was apparent from the get-go that Cynthia had no plans to start the process of dying. She made copious phone calls over the first few days to let clients know the show would go on, (much to the dismay of her daughter and me) although there was no possible way she could attend a prenatal visit, let alone anyone in birth. She could not use the stairs and she was in a good deal of pain, even with the pain meds. Her daughter and I exchanged more than a few glances of frustration. I had never seen anyone more determined to stay in this realm than Cynthia.

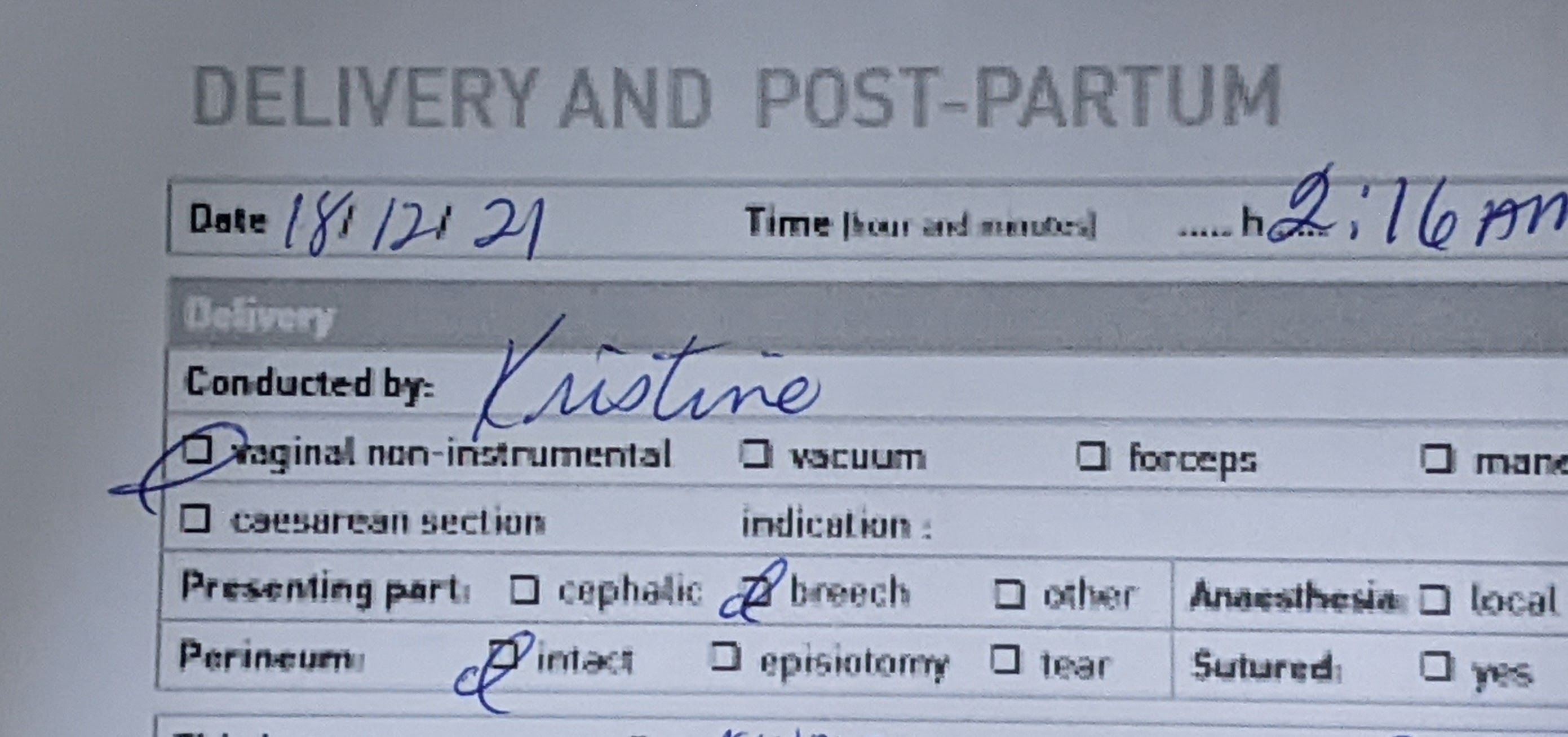

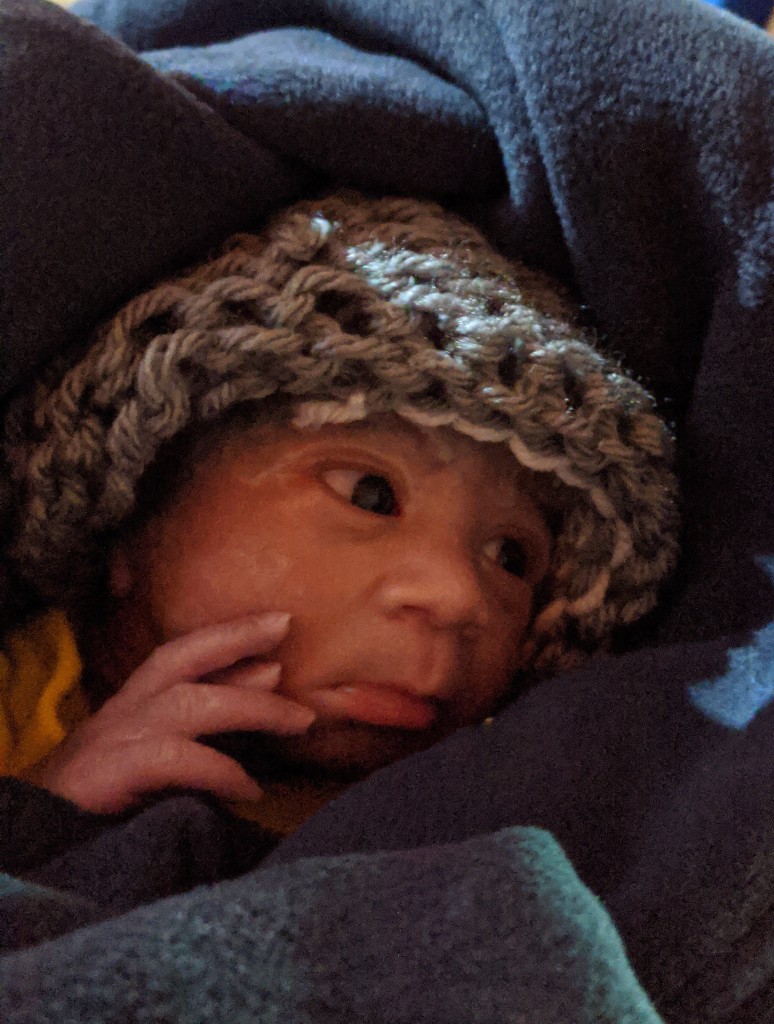

Saturday evening when the first client called and said they were in labor and coming to the birth center, I readied myself. When we heard them arrive, Cynthia was sitting on the edge of her hospital bed with wide eyes and a determined look and said, “I have to go down there”. I looked at her and said, “I know you want to but there is just no way you can ever make it down the stairs, it’s too much. I know this is hard. I have it covered. I’ll keep you posted and I’ll let you know how things are going”. This did not stop her from texting me every 5 minutes for the 30 minutes it took the client to birth her beautiful little girl. The Amish always make birth look easy.

Cynthia was already drifting off to an exhausted and opiate-induced sleep by the time I went upstairs. But I recounted the birth, minute by minute with as much detail as I could remember and saw her face soften as she imagined the scene, a scene she had lived thousands of times over in her 54-year career.

For people who never had the pleasure of knowing or even meeting Cynthia, it needs to be said that she was an incredible force in the world and especially in the birth community. Her wisdom is legendary and so is her reputation. When I first met her, 30 years ago, she told me she was a pariah. She told me I would be judged just for being in her orbit. But I knew a wise-woman when I met one and if she was willing to teach me even a fraction of what she knew, I was willing to be an outcast along with her. Even now, now that I have caught up to her in terms of ‘numbers’ of births attended, I still learn from her. She was hands down the most knowledgeable and skilled midwife by far, that I have ever met. She was also quiet humble and despised any kind of notoriety. She was a traditional midwife in the truest sense of the words and served families and had no other agenda than to meet women where they were in their process and honor their path and respect their autonomy.

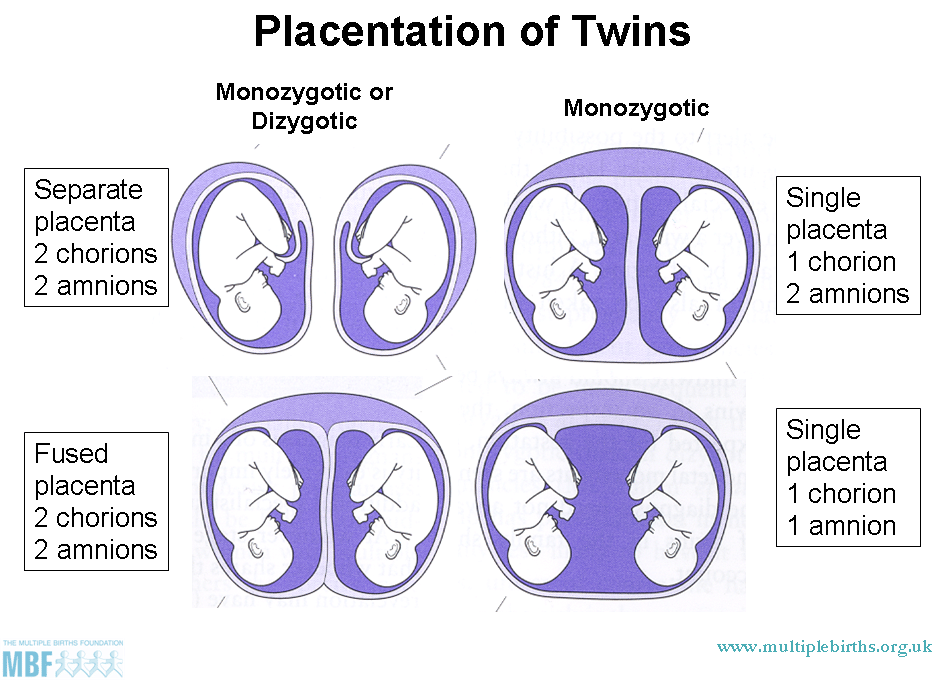

I learned the finer points of breech birth from her. I learned when to intervene and when to sit back. I learned that women who had had multiple cesareans could indeed go on to birth vaginally as long as they had the right support for their birth. I learned the nuances of attending sets of multiples and I learned how to stop postpartum hemorrhage with no medication at all. Cynthia was a gifted herbalist and knew plants inside and out. Native American on her mother’s side Cynthia’s maternal great-grandmother was Cherokee and this is who she first learned midwifery from when she was just a girl. She managed her first postpartum hemorrhage alone when she was just 14 years old.

So, it isn’t a stretch to say that Cynthia’s entire life was dedicated to midwifery. Even through a stage 4 cancer diagnosis when most people would say, it’s time to pack it up, Cynthia didn’t miss a beat. She continued to attend births. She had surgeries and she had weekly treatments. She continued to take clients. One of her last phone calls was with a woman due in March of 2023 and she told her to come for a prenatal visit the next day unbeknownst to us until the woman showed up for a prenatal visit! We had to apologize and turn her away.

When Cynthia spoke, people listened. Her voice was deep, strong and commanding. She hated appearing vulnerable in any kind of way. She had a confidence about her that took people aback at times. I saw this with the hospice nurses that came to visit. Under no uncertain terms would they be telling her what was about to go down, she made it all too clear just who was in charge of this show. After the first nurses visited for the initial intake, I walked them downstairs and out the door. I said, “Congratulations, you survived your first visit with Cynthia!”. They laughed uncomfortably and got in their car and drove off.

So, when only 2 days later, we called one of the nurses to come back to the house for a pain management consult, she was quite shocked to see a very different Cynthia. Over the 2 days since the last visit, Cynthia had made calls to clients, discussed what medications she did and did not want to take, talked about how she would have no trouble driving again once the back spasms went away, got up and cooked for herself and even fed us! She talked about plans in the spring and she had me transplant her spider plant because the pot was too cramped. What she didn’t do was talk about dying.

I have been with quite a number of people now in varying circumstances during their transition at the end of life. It is so incredibly different for everyone. The process itself is intense, curious, beautiful, strange, daunting, and wonderous. You can’t help someone die any more than you can help someone give birth. All you can do is bear witness, hold space and be there for that person in the way they need you to be which may not necessarily be the way you want it to be. You need to meet them on their terms. It isn’t about you.

A corner was turned on that Wednesday afternoon and I called Cynthia’s daughter to come to the house. Although the nurse had increased the pain meds when she visited, we were up all night with Cynthia who was in a great degree of pain which distressed us so much because it was so unnecessary. Her meds were increased and changed again and finally she was no longer experiencing that kind of pain or agitation. After that, neither of us ever left the house again and Cynthia’s son and grandchildren, some whom were out of state, were called to come for the weekend. It was apparent to us that the 4 months was a rather optimistic prediction on the part of the doctors.

Cynthia was an intensely private person throughout her life. It was no different at the end. She did not want any visitors other than her family. She did not like appearing vulnerable in any way. We had to turn people away that came to the door. In light of that, as much as I want to share some of the more intimate details of this time and her process, they are not mine to share. So out of respect for Cynthia and her family, what I will share is my experience from this time.

Once the family had gathered, I did my best to spend as much time downstairs in the birth center as possible to give them space. However, I was the one in charge of giving her meds, which happened every 1 to 2 hours around the clock, so I was upstairs a great deal. Still, it was a beautiful gathering, and I could feel the love and joy with everyone around, cooking, talking, eating and drinking. They graciously included me and I felt close to them as if we had always known each other, which was good because we were all walking through this together; this incredibly intimate and sacred journey that so few people in our society get to witness anymore. But this is how it should be and this is what Cynthia wanted and it was awe inspiring. I have so many more things to say about this beautiful family, each one of them individually, but I also want to protect their privacy.

On Friday evening, one week after Cynthia had arrived home, another client went into labor. She too came in and birthed within 45 minutes. By this time, there was another midwife who had come from out of town to be down in the birth center so I could attend to Cynthia. Still, I went down and attended the birth and when all the work was done, I went upstairs and after the 1:00am meds I sat next to Cynthia and told the birth story right down to the number of pushes and the weight of the baby. She could still hear even if her responses were minimal. It was always Cynthia’s wish that she die like her great-grandmother who attended her last birth at the age of 97 and went to sleep that night and never woke up again. This was not to be but that didn’t mean I couldn’t do my best to approximate it.

The irony of the whole situation was not lost on me. Welcoming life into the world while simultaneously bearing witness to a life leaving the world. It was an experience, a incredible feeling – the privilege that I felt straddling both ends of the spectrum in this manner was indescribable.

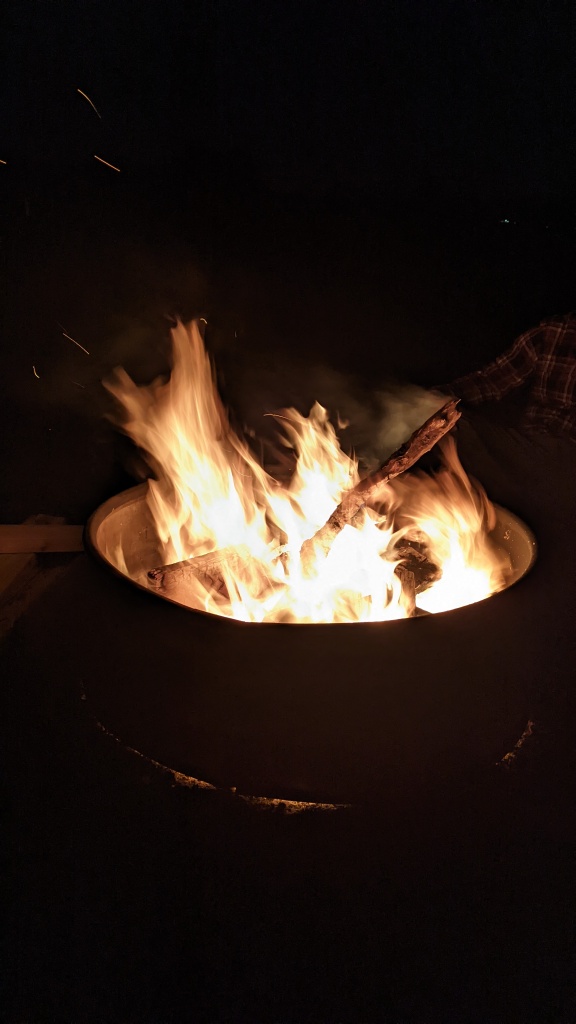

To honor Cynthia’s Native heart, the family built a bonfire on Saturday evening and played drumming music to usher in the full moon that was about to appear after midnight. We all knew this would be the time. It was a cold, crisp, clear night. Everyone was in bed by 1:30am and I came up for 2:00am meds. Cynthia’s daughter was on the sofa, half awake. I asked her if she needed anything, she said she didn’t. I gave that round of meds. I had noticed through the course of the day the difference in Cynthia’s pulse and breathing. I knew it wouldn’t be long. And for all the resistance she showed in those first days home, she was now exhibiting a gracious surrender to the process, just as I imagined she would.

At some point just after 3:00am, with the full moon shining in through the window, my mentor, my teacher, my friend, made her transition to the next place. The stillness in the room was so apparent. It felt so empty. Her presence, larger than life even while dying, was so palpable, that once she took her leave, her absence was profoundly felt.

During the week when all of this was taking place, there were so many things going on behind the scenes. Mutual friends of ours were texting me, supporting me from afar. I did not ask permission to use names, but they know who they are. C, L, DA, B, J, D, V, all of them midwives, all of them midwifing me though this experience. I am so grateful for every one of them. Cynthia had given all of them had a tiny piece of the puzzle, which we realized later once we all put it together.

L told me that Cynthia had called D to come and help with births because she knew if D came, she would want to move back and take over the birth center. That is exactly what happened. B told me that Cynthia had told her a while back, she wanted drumming when she was transitioning. I told this to her family, and we made it happen. We would not otherwise have known. Cynthia did not speak to me at all about what she wanted during her transition so I could only piece things together from the tiny bits she gave to other along the way.

I never had any profound bedside chat with Cynthia during her process because that was not how things unfolded. Everyone thought there would be months, I think, so we were all operating on that assumption until we weren’t. And she herself was not in a place where she wanted to discuss it. But on one particularly lucid conversation over the phone from the ICU, before she came home, she started telling me how far I had come from when she first met me. How I had come into myself, found my feet and what a presence I was in the birth world and how proud and how happy she was for me. I realized later; these were things she needed to tell me. This had been the bedside chat. They were not necessarily things I needed to hear, although it was nice to hear them. She always worried about me just a little bit. She needed to reassure herself that I was going to be okay without her.

It was that conversation I realized, looking back, when she chose me to walk her home. She knew intuitively that I was up to the task. She knew I would care for her family in the way she wanted – that I would be unobtrusive and respectful. She knew how vulnerable she would be and that I would protect her. She knew I would have her back, whatever that meant and whatever it came to. She knew I would advocate for her if it was needed, and it was, and I did! She knew I would see her on her way with grace, dignity and respect just the way she did with the thousands of women she served. She knew she had taught me well. Of all the things I learned from her, of all the gifts she gave to me, this last one was probably the greatest.